111 for 30 #006 - Catatonia 'Strange Glue'

A 90's rollercoaster ride of pop genius and strange meetings.

PLEASE NOTE: This isn’t an official BBC / BBC Wales post. All words / opinions expressed here are my own.

Key links: https://www.cherryred.co.uk/product/catatonia-make-hay-not-war-the-blanco-y-negro-years-5cd-box-set/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catatonia_(band)

The second time I met Catatonia was one of the strangest nights of my life. It was one part Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, one part Johnny Vegas fever dream.

It was the first - and one of the very few - industry beanos I’ve ever been on. One day I’ll tell you about the humiliation of EMF’s second album launch party at a rowing club on the Thames. We don’t know each other well enough, yet, for that story. Perhaps we never will. Cross your fingers.

Or the night I was snubbed by the cast of Hollyoaks only to get into a hotel lift and have Dave Grohl ask me which floor I wanted. But this low-rent namedropping doesn’t become me.

Catatonia were one of a number of nascent Welsh bands playing at the In The City seminar in Manchester in 1994. I wrote previously about 60ft Dolls changing my life that self-same night here. I don’t remember seeing Catatonia play at In The City but I’m sure I must have. I’d fallen into the orbit of 60ft Dolls’ drummer Carl Bevan and things started to get really strange from then on in.

Carl has napalm charisma and polymathic abilities that range beyond being a brilliant drummer. He was an amateur taxidermist; has become - in recent years - a lauded and successful, self-taught painter; and is a great conversationalist (perhaps his eloquence and wit came from his dad, the legendary preacherman, Ray Bevan). Carl also had an incorrigible sense of mischief… he was, back in those days, a one minute past midnight, feasting gremlin possessed by a brandy-fuelled poltergeist.

I can’t tell you the story about the hospitality beer in the Carlsberg tent at Phoenix Festival in 1996. Never ever trust a replaceable cap, is all I’ll say. Look for an unbroken seal. Every time.

In retrospect, the fact that two of the Dolls liked a drink became an obstacle to them being embraced for their musical excellence. The music papers ran pieces about their high street hedonism, barely mentioning the band’s fierce, rare alchemy.

We all drank in the 90’s. It wasn’t ‘just’ lad culture. I wouldn’t have been at all comfortable with that lairy bullshit. But alcohol was an inextricable part of the culture I grew up in, and the Dolls too, I imagine.

Number One Pure Alcohol - their second single - was an Asheton-riff fuelled call for help, not a call to an eternal lock-in, in retrospect.

That it became central to their story was depressing in the extreme. It became a creature that fed itself, self-fulfilling. Wherever the Dolls went, free booze rained from the ceiling.

I suspect that the same could be said for Cerys Matthews.

If there’s one image from those early years of my show that stays with me, as much for its boggling and oxymoronic wrongness as anything else, it’s peering down at Cerys as she crawled along the floor of the venue in which we were gathered, very intent on the swirling patterns in the carpet.

I was holding Ray Davies’ hand. He was asking me about my band’s manager, Lola McGrath Lavegie. She’d told us that she’d known Ray and that he’d named his song after her. That story - one of many - had been imparted when my band and I had first met Lola at the 48 Boulevard in Cogolin. We were naive bumpkins but we weren’t stupid enough to believe a word of that fairytale.

It was something of a surprise, then, to meet the man himself, having been thrust at him by Carl, and to hear that the story was true, bending an already over warped sense of reality.

And still Cerys inspected the weave of the carpet, necessitating Ray to step over her without a word of complaint.

He continued to hold my hand. His was the hand that wrote Waterloo Sunset, my musical sperm and egg. Carl swigged out of a bottle of brandy he’d liberated from somewhere. Cerys was trying to light a fag, but it was the wrong way round. Everything went hazy and super weird.

If the Dolls were my favourite live band from that period, Catatonia were - by some margin - my favourite studio band. They had recorded an unholily brilliant session for my first run of programmes in the winter of 1993. It was recorded at the Tannery Studios in Oswestry. Producer Jane and I visited them as they recorded but we didn’t have anything in the way of conversation. They were too busy in the live room. Mark’s black Rickenbacker made me jealous to the pit of my stomach. And I thought that Cerys was just about the coolest human being I had ever encountered.

Like Carl, her charisma fair exploded out of her. And that voice… I remember someone at the time trying to describe it as kitten-ish, Bardot-like, but if Cerys had any kitten-like qualities she was a kitten who could roar, scale your teeth with the power of her voice. She thrived in an industry that is sexist to its core, and she seemed to do that entirely on her own terms, and still does.

I know a bit about what goes on under the bonnet of radio programmes, about how presenters are often driving other people’s music knowledge and application, but Cerys’ programmes on 6Music are so obviously woven around - first and foremost - her passion and curiosity for music.

It’s the most listenable and revelatory music programme on the UK airwaves, to my mind.

Anyway, I digress.

The Tannery session for my show, recorded by Ken Nelson who went on to be Coldplay’s de facto engineer and producer for their early albums, was the early Crai Records line-up of the band. Clancy Pegg was still playing keyboards for them. I think the drummer that day was Daf, who then went on to join Super Furry Animals.

I liked Clancy’s contribution to Catatonia’s early EP’s. I particularly loved a song called ‘Fall Beside Her’ that combined Mark’s chiming guitars, Cerys’s Gitanes on the banks of the Seine insouciant vocals, with the throb of Clancy’s analogue synths.

Somewhere along the line Clancy left the band when they signed to Blanco Y Negro. As Catatonia then went on to record one of my favourite debut albums of all time it would be churlish to remark on what could have been had they and Clancy stuck together. Maybe they’d have stayed in the leftfield, more in the vein of Broadcast or Stereolab.

Little - however - has been as exciting in the 30 years I’ve been broadcasting than Catatonia’s ascent to the very top of the charts. Their success as a bona fide pop band was absolutely thrilling.

But I’m getting a little ahead of myself.

I interviewed Cerys to coincide with that initial session broadcast. She was charm incarnate and described the Laura Ashley furniture in her hotel room in Shrewsbury in gleeful detail. She gave little away about the music. Our most intuitive artists rarely want to talk about the pragmatic details of what they do. There’s an innate understanding that less is more, that a swirl of mystery is more enticing than a list of ingredients and cooking instructions.

On another occasion, round about the release of ‘Way Beyond Blue’ (but please remember my usual Previn / Morecambe proviso about me having all the right memories just not necessarily in the right order) Cerys came onto the programme to talk about some of the music that had been inspiring her. She chose five songs and I remember them being invigorating and Catholic choices, highlighting the adventurous, genre-vaulting tastes that she’s now synonymous with on her radio show.

Three of her choices - in particular - stand out: Snoop Doggy Dogg’s ‘Gin and Juice’, Brian Eno’s ‘Here Come the Warm Jets’ and Lynn Anderson’s ‘Rose Garden’.

At this point in time, 1995 or 1996, not many of the supposed indie crowd were paying any attention to hip hop unless it was filtered through The Beastie Boys or DJ Shadow. Cerys heard the humour and genius in Snoop and Dre’s recordings and was just about the first person to make me reassess my antediluvian attitude to what was often pejoratively called ‘gangster rap’ back than.

Cerys prised open my mind and taught me a valuable lesson about broad-mindedness.

See also Eno’s ‘Here Come The Warm Jets’. I can’t say that I love the entire album, but the title track has stayed with me and proved to be a joy and inspiration since Cerys’ recommendation. It became a gateway to Eno’s other work and into ambient music with substance.

Anderson’s ‘Rose Garden’ had been a staple on Radio 2 when I was growing up. One of those songs - like ‘Forever in Blue Jeans’, ‘Kisses for Me’ or ‘Wichita Lineman’ - that I knew every word to, before I knew how to wipe my own bum. Cerys wasn’t picking the song ironically. She loved country music, a fact that was crystallised by the latter two Catatonia albums, the love of bluegrass and country soul that coloured some of her solo work, and - subsequently - her radio show.

Despite the 300 mile round trip I spent a lot of time in Newport between 1994 and 1996. I felt more kinship with the musical community there than I ever did with the music folk in Mold or Chester. I remember a lot of laughter, a lot of drinking and a lot of really good, unpretentious music in venues that embraced their scuzzy clientele rather than just plain tolerating us.

One night in TJ’s (naturally) a little buzz went around those of us present. Mike Cole (60ft Dolls, cover of ’19' magazine) and Cerys had tumbled in together. This would have been well before Catatonia’s Top 10 releases. There was something magnetic and freewheeling about the two of them. They whirled around the pool table with something of Suzie and Bob in the constellation they made, or Juliana and Evan.

When the doors had opened and they fell in through a curtain of sodium-tinted Newport rain, their ineffable star quality lit the room. Those of us present were a ragtag bunch of Kellys Zeroes, aspiring musicians destined to ‘fail’ in that respect. We just didn’t have the aura. So few do. No one resented them for it, I don’t think.

Some time around the release of ‘Way Beyond Blue’ my best friend, Richard, drove us up north to see Catatonia play in either Leeds or York. I can’t remember which. Mostly I emotionally manipulated Richard into chauffeuring me places under the very questionable pretence that we might create an opportunity for our band (Rich was on bass, b.v’s and Jam jumps).

No opportunity was ever forged by these hare-brained escapades. Not one. We were both cocky gobshites on our own turf but the bravado evaporated anywhere further than 6 miles from Mold, severely limiting our networking effectiveness.

I remember Catatonia being brilliant that night. A promo of the album had become the cuckoo’s egg in my portable CD drive. I especially loved the more expansive, shape-shifting album tracks that were never destined to become singles. ‘This Boy Can’t Swim’, ‘Infantile’ and the title song still put a gentle charge through my soul, casting things in woozy, captivating ellipses.

Cerys’ voice is a monument to those times, and I love her presence, her charisma and the sense of sublime mischief she had about her. Much as I admire the success and craft of their chart conquering second album, ‘International Velvet’, it was the debut that entranced me and continues to do so.

Their Cymric skew of Pixies on ‘This Boy Can’t Swim’ is as good as anything I heard from anyone back then.

Rich and I watched them. I was awed. Rich - less easy to impress - doesn’t even remember the gig. It’s funny how we experience things so differently, isn’t it?

Rich and I got drunk after the gig. The woman who owned the B&B thought there was something biblically untoward going on when we tried to stumble up the stairs back to our double bed, giggling, in the early hours. She stood in the hall watching us derisively, tapping her foot like Maria in Jet Set Willy.

When we got up in the morning, the communal TV violated our hangovers with footage from a Tory party conference. Iain Duncan Smith and William Hague looked like throwbacks. We laughed at them, at their privileged barricade-manning. They seemed so utterly unelectable, so far removed from our times and sensibilities.

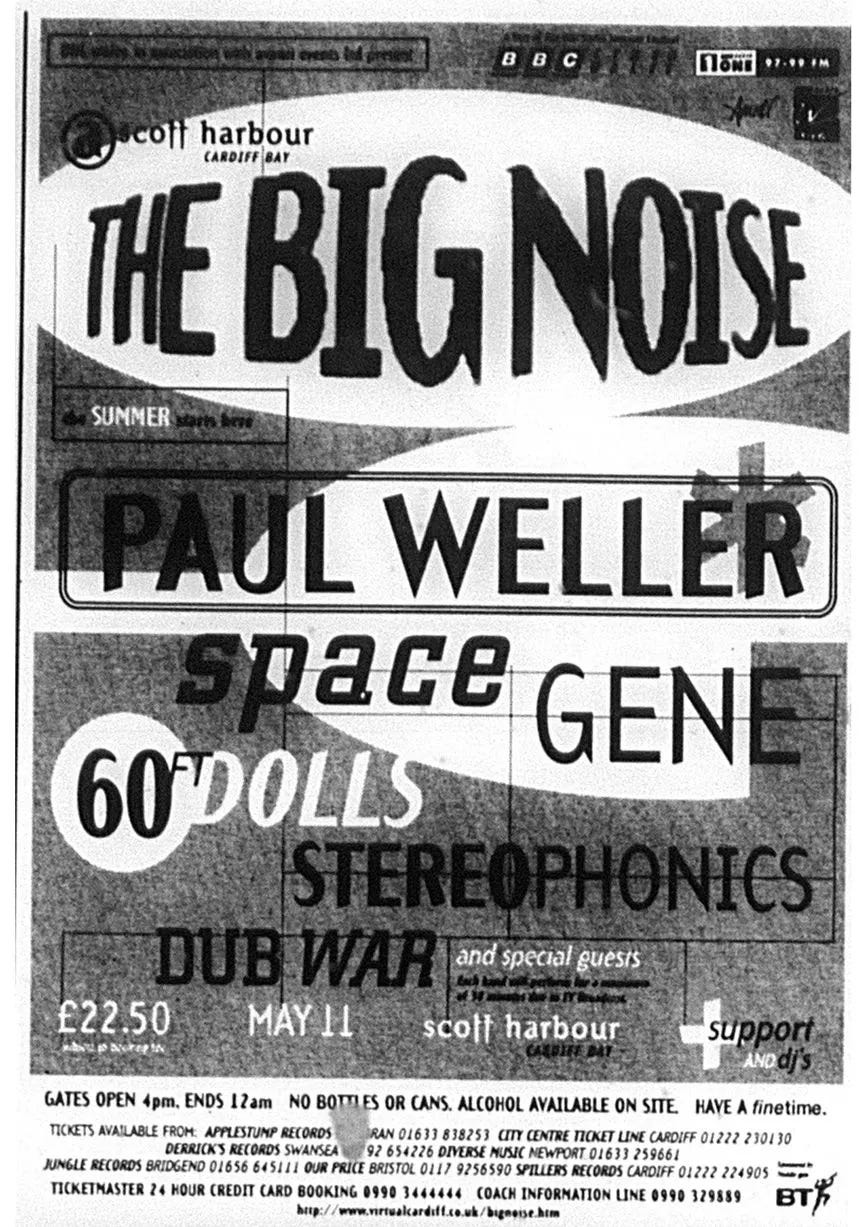

Scroll forward to May 1997. BBC Wales broadcast a huge event from Cardiff Bay that has somehow managed to capture the zeitgeist of a new found confidence in Wales. It’s called The Big Noise. Paul Weller headlined a floating stage in the middle of the bay. I got to carry one of his guitars into the dressing room, sneaking in alongside 60ft Dolls’ front-man Richard Parfitt, who has known Weller since his first band - The Messengers - blagged their way onto The Jam’s ‘Bucket and Spade’ tour some years previously.

Paul was personable and relaxed, as was his dad and manager, John. I was pretty awestruck but shuffled off before I was asked to leave because I had to interview Catatonia.

There was a really strong Welsh presence on the bill: 60ft Dolls, Dub War, Stereophonics, Noel from Hear’Say and Catatonia.

I remember Cerys walking through the production area where I was to interview her, swinging a can of lager and resplendent in what I thought was a shell suit, but actually transpired to be a Man Utd away top. This was awful news. I’m a diehard Liverpool red. It was like discovering your mum had snogged Nigel Farage. Oh fuck, no! Not that bad! My mum was light years out of his league.

Cerys’s get up - the footie top, trackie bottoms and sovereign rings - was a quite a statement for the times. She adopted the garb of underclass Wales at a time when too many artists and cultural commentators were quick to be dismissive, use the ‘chav’ word.

It was an impressive demonstration of quiet solidarity (in that she didn’t then talk about it, at all. Show, don’t tell.)

‘Way Beyond Blue’ did well for Catatonia but in a time of eye-watering advances (record company newspeak for ‘overdrafts’) their label would have demanded more than a couple of top 40 singles and a growing fanbase. The pressure was on for a follow up that would make good the label’s expectations and outlay. I’m not party to the details, but I think that the band had - to all intents and purposes - been given a last meal and cigarette by Warners, who repeatedly delayed the release of their second album as they shifted priorities and tried to distance themselves from a ‘project’ they had stopped believing in.

This was how the music business operated in the mid-late 90’s: human beings, their art, wellbeing and souls were of secondary importance to catching the zeitgeist next time round: a whole host of second-guessing surfers constantly missing waves and the responsibility they should have been shouldering to generate them.

The first single from Catatonia’s second album, ‘I Am The Mob’, therefore arrived with no fanfare whatsoever. This was a time, remember, when even leftfield bands like The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion would announce a new release with promo merchandise. Theirs was either a bowling shirt emblazoned with the JSBE logo or a tabletop lighter resplendent with spinning blue and red neon lights.

These were the last days of Rome for the music industry as was: all excess and ludicrous promo budgets that filleted the bands they were supposed to be enabling.

However there was something thrillingly chaotic and non-careerist about these Bacchanalian days. And the pervasive belief amongst many aspiring music-makers that if you made a noise worth listening to, then an A&R would hear about it and sign you. And if the deal was shit, so be it… it didn’t really matter as long as you got your ticket for the star spangled gravy and coke train.

Artists barely talked about their ‘art’. It was still rock’n’roll. Coolness, feigned indifference, were the order of the day. No one - not a single artist - would have dreamed of filling in an application form for funding. The dole meant we didn’t have to.

Because it’s incumbent on all old bastards with tears in their rheumy rosy eyes to bemoan how things are so much worse now than they were in our time, this is the hill I’d be happy to die on, if I could drag my wheezing proto carcass to the top.

i miss character and gnarliness being more important than marketability. I’m sad that some artists use the word ‘application’ when they send me music. I’m not blaming them. This is the landscape that ‘we’ have created. Knowing how best and effectively to fill out an application form now outweighs the ability to write a chord sequence that can shift the universe half a degree to the left (always to the left), or a hook to hang someone’s dreams on.

It isn’t what I signed up for.

Catatonia came and played The Tivoli (the Tiv) in Buckley in the months while ‘International Velvet’ was in limbo. I was in a bad way. I wasn’t sleeping, my dream of making a livelihood through music had crumbled in my grasping fingers. I was struggling to come to terms with grown up responsibilities. My best friends weren’t talking to me. I was drinking too much and necking pills to hang on to a semblance of good feeling. Lost… temporarily (as it transpired) and self indulgently (no doubt), but lost all the same.

I snuck into the back of the venue very unkeen to be seen by anyone I knew. I watched the band from just behind the mixing desk. They were good… they were always ‘good’, it needs to be mentioned what a fantastic ensemble Catatonia were… no gristle, everything in service to the power of the song… but something felt awry. Paul usually buoyed things along with frequent smiles that outshone the lighting rig, but that night the smiles were sporadic, forced. Cerys looked like she was going through the motions. It felt a bit unspecial but the likelihood is that I was experiencing this all through the dark grey prism of my own comedown.

Mired in doldrums and bad feeling as I was, I can still remember Owen playing the intro to ‘Strange Glue’ and the overwhelming effect that those dolorous, captivating arpeggios had on me.

That moment - the sound, the lights, the crowd, the band members - expanded to fill all of the emptiness that had been my four compass points for months. By the time the song had finished I was quivering, and alive.

I sat in my mum’s Fiesta in the carpark outside the venue and cried. All of the things that had felt hopelessly lost had returned. One song did that. What a sap.

[‘Strange Glue’ was written by Catatonia guitarist Owen Powell. On this week’s programme (2nd March 2024) he gives us a fascinating insight into the song in our regular ‘Behind The Track’ feature.]

By the time Catatonia played in Llandudno in April 1998, ‘International Velvet’ was resplendent at the top of the UK album charts. To say that they’d been vindicated, and that you could hear the sound of their label shifting priorities back around to embrace the success that they obviously always believed the band were going to have, would be a colossal understatement.

Llandudno was - to all intents and purposes - a hometown gig for Mark and Paul, who both originated from Llanrwst.

My ex-wife, Jo, and I drove to Llandudno early. We were both fans and excited to share the experience of seeing them at this celebratory moment in their existence. I also had an interview slot with Cerys and Paul.

As befits all bands entertaining friends and family when they come home to play a gig, the interview slot kept getting pushed back. I was becoming more and more nervous, but - eventually - uncles, aunties, nephews and nieces, former school teachers and old classmates ambled out for pre-gig pints and nourishment, and my wife and I walked into the green room, portable MiniDisc machine at the ready.

Cerys and Paul were so happy, so relaxed. I can’t remember ever having encountered a band in similarly joyous circumstances… I mean, they weren’t showy or spraying champagne over each other… there was just a happy confidence about them. Cerys was lovely to Jo, who she’d never met before. I’m sure half the interview time was taken up by them both talking about whatever it was that they were both wearing. Paul and I did not do similarly.

There’s a transcription of the interview here. It’s not at all that revelatory but it does capture them in that moment, and for that reason it was worth searching through a mountain of MiniDiscs to rediscover and transcribe.

The story gets a little messier now. And I’ll have to rush the end. Four thousand words is time neither of us is going to get back from this cruel universe.

I started a record label in 1998 - Whipcord Records - because I wanted to “give something back”. Also the BBC’s conflict of interest rules were either non-existent or hadn’t been explained to Steve Lamacq. It seemed like a thoroughly decent thing to do but it was also one of the worst financial decisions of my life. Mainly due to my debut release being a 7” single from a band whose singer moved to New York two weeks after release, leaving me with 450 unsellable copies of their 7” single.

They didn’t even pay me manufacturing costs for the box of 50 singles I let them have under that agreement. And I was left with a hill of completely unnecessary paperwork because I listened to their manager’s advice and set up a Ltd company, instead of just releasing the single as a sole trader.

The demands for accounts only stopped arriving on my doorstep after I moved. Actually, they’re probably still arriving at the old address on Whipcord Lane.

But - again - I digress.

The ‘Out’ (that was the name of the band) farrago left me £2000 out of pocket on a meagre income scraped together from presenting one show for Radio Wales and one DJ slot a week. My ex-wife’s income bore the brunt of this financial body blow. I don’t think she’s ever really forgiven me for that. And I don’t bloody blame her.

Thankfully the next two releases on the label both sold out: Big Leaves’ brilliant ‘Sly Alibi’ and ‘Racing Birds’ singles.

I will write about Big Leaves - my part in their downfall - at a future date if Putin hasn’t got us by then.

Big Leaves were invited to support Catatonia at their massive Home International shows in Llangollen and at Margam Park.

These gigs - especially the two in Llangollen, where the weather held and didn’t turn proceedings into a mudbath (which is what happened at Margam Park) - were for me the apotheosis of what had been boiling up in Wales over the preceding four years. You’ll notice that there’s a particular phrase I’m not using that became associated with those times. It was never embraced by the people responsible for the music. Often that cheap piece of alliteration was something the headline writers in publications who hadn’t shown the remotest bit of real interest in Welsh music up to that point, used to make hay while that particular sun shone. Which - as mentioned - didn’t happen, somewhat symbolically, at Margam Park.

My abiding memory of the Llangollen gig wasn’t how good Big Leaves, Shack and Catatonia were, and they were all great, amongst a febrile sea of celebratory audience-fuelled joy. It was playing acoustic guitar backstage with Richard Parfitt from 60ft Dolls and Catatonia’s Owen Powell.

I always wanted to be one of them and this was as close as I ever got.

As good a place to end as any.