It will be the 20th anniversary of Elliott Smith’s death on the 21st October 2023.

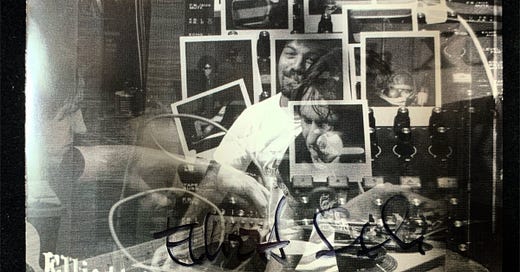

I had the good fortune to meet and interview Elliott on two occasions (at the Academy in Manchester in April 1999 and - by his invitation - in London in 2000, in the run up to the release of Figure 8). I will write in more detail about those interviews in due course.

No artist has had a longer and more profound effect on me than Elliott. I hope the anniversary creates more opportunities for his music to be enjoyed and talked about over the coming months. I’m also mindful that his loss continues to be unresolvable and raw for his family, friends and fans, especially given the circumstances of his death. I just want to write about Elliott and his songs.

If you want to read about Elliott’s life, the two biographies that have thrown most light on him for me are ‘Torment Saint: The Life of Elliott Smith (2014)’ by William Todd Schultz and ‘Shooting Star: The Definitive Story of Elliott Smith (2023)’ by Paul Rees.

Full disclosure: I will be interviewing Paul on BBC Radio Wales on Tuesday 5th September, but I only arranged that interview after buying the book, reading it, and recognising what an authoritative and excellent job Paul has done in telling this most difficult and sensitive of stories.

It feels important for me to try and quantify what is in essence unquantifiable: why Elliott Smith’s music means more to me than anyone else’s. That’s quite a statement, I suppose, from someone who’s paid to stay open-minded and hungry for revelations in new music.

Elliott is one of the few artists whose songs I return to cyclically, like a swallow migrating: The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Husker Du, northern soul, Kelly Lee Owens and The Joy Formidable would be some of the others, but it’s Elliott’s work I come back to most frequently.

How can songs that came out of such anguish and bitterness prove to be my comfort? I don’t really know, and that’s one aspect of his work that I’d like to understand better.

I don’t think it’s anything as simple as catharsis. Catharsis feels like a very selfish response to music that has been bled out of someone else’s sadness and pain. I do understand that Elliott’s songs are characterised by more than pain and sadness. When I met him, he was gentle, funny and passionate about his new albums… especially when we got talking about the recording process or The Beatles.

My very limited experience of Elliott was that he was happy to geek out about music, recording technology and the differences between UK and US cigarettes. I didn’t try to push the envelope further. I’m no journalist and I wasn’t after a story.

In preparation for the interviews, all I did was listen to his music. I hadn’t read about him… I knew about the Oscars ceremony appearance, but wasn’t interested in it. I knew there was a melancholic heart to his songs, but the same was true of all of the music that I most loved.

A lot of the time I’m initially drawn to things on a superficial level. Melody and feel rule my musical heart. Lyrics and nuance in the words are the last things to register. Perhaps that’s why I walked along with Elliott in my ears for quite some time before I started to hear the undertow of pain beneath the intricate beauty.

It was Elliott’s gentle, whispered delivery (not always, but mostly) that made me fall for him hard. It’s a sound that suggested to me a soul brother, someone who - like me, I felt - was making music to keep the world at bay. The reasons for his making music wouldn’t have registered if he hadn’t also had a gift - one of the greatest gifts - for weaving his voices and guitars together. The boundaries between the songs almost don’t matter, it’s those sounds that have either buoyed me along or that I’ve clung onto, depending on circumstance, over the decades.

Initially I was most drawn to his double tracked vocals, especially on ‘Roman Candle (1994)’ and ‘Elliott Smith (1995)’.

Double tracking is exactly what it says on the tin. It’s when an artist records two - or more, sometimes many more - iterations of the same thing onto different tracks in a session for a song. Why would you do the same thing twice? Well it can thicken up - smooth - frailer voices and give a more pleasing quality to a vocal. It has been part of the recording engineer’s armoury since multitrack recording started in the early 60’s. The Beatles became so sick of recording double tracks that their engineers invented ADT, an automatic way to achieve the same effect, because as much as it was a pain in the arse, they also liked the sound.

Elliott must have liked the sound, too.

If you listen to ‘No Name #3’ on his debut solo album, his voice is simultaneously sublime and lonely. It sounds like the one star that manages to peep through an otherwise occluded sky. Even on that sketchbook debut album, insular, raw and untempered, Elliott’s supernatural gift for melody is abundant.

His melodies are rarely showy, McCartney-memorable melodies. They gloam over unfamiliar chord sequences, parallel to, but a step removed from, the rest of the rock ’n’ roll canon.

His melodies are as unique as fingerprints. Insidious. Beautiful. Fragile.

I suspect, though, that if you stripped away the vocal line from ‘Needle In The Hay’, as one example, that it would lose much of its ability to billow the heart with sad yearning. It’s almost always the counterpoint between the vocal lines and Elliott’s genius guitar playing that elevates his songs.

They are luminously dependent and symbiotic.

If you don’t know, his first two solo albums were - by no means - his first recorded efforts. There had been many high school bands and home recorded cassette albums before Elliott got to his breakout band, Heatmiser.

He’d already put his ten thousand hours in, and then some, by the time he released his first solo album.

Words like virtuoso and genius aren’t my hyperbole. Elliott’s gifts awed his friends and peers right from the off. Reading both of the books referenced above, you get an impression of someone who was incredibly driven and dedicated to his cause. Whatever the DNA of his songs, his ability to write them and play them was borne out of absolute application to the craft, even if that word might have been anathema to someone who was also steeped in a hardcore and DIY punk ethos that had to deliberately undersell virtuosity to be relevant and cool.

Double tracking the guitar and voice is such a key part to Elliott’s sound, especially on the first two albums. It gives the recordings a width that we, as listeners, are invited into, without resorting to the usual production tricks afforded singer-songwriters, namely a lot of reverb to smooth things out and give the listener an impression that they’re in a room with the artist performing the songs.

Elliott’s songs - however - are right there, right inside your ears. No barriers.

Often musicians resort to double tracking to cover a certain amount of ineptitude. Record two guitar tracks of exactly the same part, and pan one hard left and the other hard right, and it’s likely that a mistake or inconsistency in the left channel will be masked by the take in the other ear. This can add texture and it’s perfectly acceptable, standard recording practise.

Elliott, however, wasn’t using double-tracking to cover up a lack of proficiency. I suspect he just liked the sound it created, the sense of space it conveyed without distance.

His guitar playing is quietly extraordinary. I can imagine him sat in a darkened basement perfecting those takes for the first couple of albums, with no one to please but himself.

John Lennon - famously - wasn’t a fan of his singing voice, and used double-tracking and studio trickery to mask his vulnerability. No wonder that Elliott - as a Beatles obsessive - did similarly. The layers of his voice sound so beautiful… impressionistic and yet defined, somehow. A significant breathy whisper that took some of the edge off the bilious lyrical content… sugaring the pill, you might say.

His voice is also capable of great conveyance with little melodrama. He’s the dark matter Mariah Carey, in that respect (as well as many others, no doubt). When his falsetto cracks on ‘Christian Brothers’ it brings real gravitas to the recording, especially when it’s almost immediately balanced by a heavenly twelve string guitar part that sounds like poppies bursting through broken concrete.

He really knew how to do an awful lot with relatively little.

I love the adornments and embellishments of his later albums but I can also hear why so many of his most ardent fans prefer the apparent baseline simplicity of his first three long players.

We feel like we’re party to something private in those recordings, especially. Unadorned and precious, and who doesn’t love being imparted secrets?

I know many people who revere his songs and music but I have never sat down with any of them and discussed our draw to Elliott Smith. Probably it’s the intimacy of the relationship that we develop with his songs and recordings that gives us a sense of something private and special between us. Something it’s not easy to elucidate (as you’re experiencing).

So much of our lives, in 2023, is chronicled and detailed to the nth degree. Anything that transcends this anathema to mystery becomes automatically more precious.

Obviously I can see the glaring contradiction in my writing that.

As we approach the twentieth anniversary of this death, it’s timely - I think - to reflect on what still makes his music so special. Those of us who are fans are evangelical about the fact. If - somehow - you’re reading this but don’t know Elliott Smith’s work, then don’t waste any more time on my pontificating. I won’t deign to suggest a starting place for your listening. It’s almost all great. My only advice is that you listen in private and immerse yourself in the music. His songs stand out in playlists, but they resonate most loudly in the context of the original, entire albums.

Finally, for now, I hope this anniversary is also cause for the music industry to re-appraise its responsibilities to artists and the stresses that are still routinely imposed on human beings who are - often - most special to us because of their sensitivity.

On the basis of what I’ve read, the industry - the labels, managers, agents, journalists, DJ’s et al - weren’t responsible for Elliott’s fate. He’d exhausted so much goodwill and love by the end of October 2003. His friends and family obviously loved him, but it must have been hellish well before that awful night on the 21st October. I can’t imagine what it’s like to love someone but to be at a complete loss as to how to help them. Sometimes people are just too damaged to fix.

I hope that now, twenty years on, there is more understanding and support for addicts and damaged people in the music industry. That - at least - would be something positive that could be part of Elliott’s legacy, alongside his incredible body of work.

Thank you to Gareth from JustPlayed for telling me about Paul Rees’ book.

This is not a sponsored post. There are no affiliate links. These are some of my thoughts on Elliott and his music.

Elliott’s the only musician I ever followed on tour. He meant the world to me.

Excellent article. I was at that Manchester gig and I think Either/Or and XO are his strongest works, but thank you for reminding me of his earlier albums which I will dig out and enjoy again. He is much missed here.